CEX shares his Reflections on the IOI Conference 2024

In May I attended the International Ombudsman Institute (IOI) Conference, which took place in The Hague, hosted by the National Ombudsman of the Netherlands.

As the global network for ombudsman schemes covering public services, the IOI provides a great platform to gain an insight into current practice around the world, and the four themes of the conference – Climate Change & Living Conditions; Value Dilemma’s; Outreach; and Future Generations – gave an opportunity to see how colleagues are dealing with some of the most pressing issues.

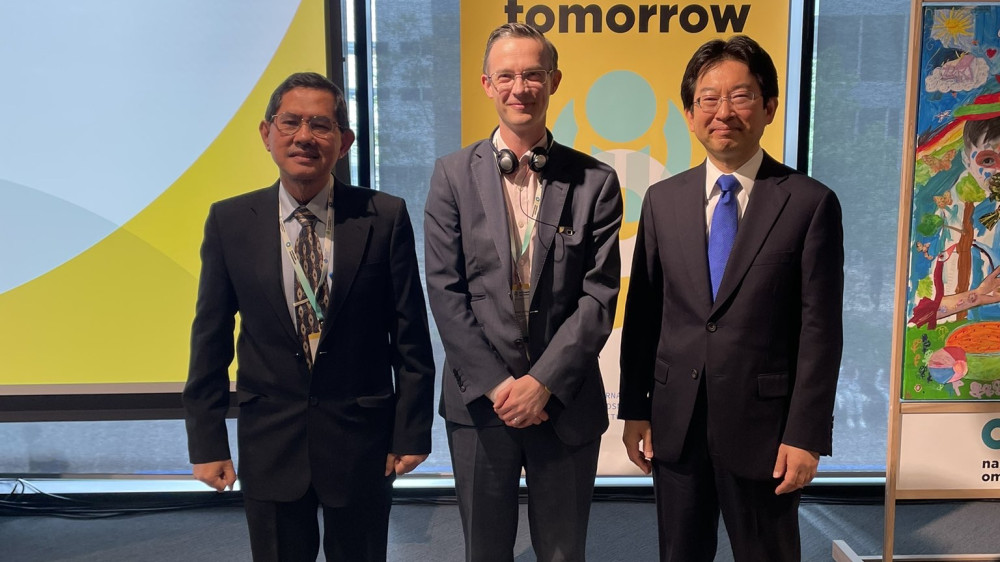

I chaired a session on ‘Making use of volunteers in your outreach’, with presentations from the Vice Chairman of the Indonesian Ombudsman and from the Deputy Director-General of the Japanese Administrative Evaluation Bureau (the equivalent of the ombudsman system in Japan).

Whilst utilising volunteers is not an entirely alien concept to our members (the UK Pensions Ombudsman have a sophisticated volunteer network of over 200 pension professionals dealing with casework), it is perhaps not a common one, so there was much in the Japanese and Indonesian approaches that our members might find it useful to reflect on.

The Japanese model exists in lieu of a ‘classical’ ombudsman system. The Administrative Evaluation Bureau (AEB) is part of a Government Ministry (of Internal Affairs and Communications). With a small central team of civil servants dealing with complex cases, the key element of the system is 5,000 unpaid volunteers nationwide, with at least one based in every municipality. Receiving complaints, providing advice and signposting, and mediating with the relevant government office, the system of ‘Counsellors’ perhaps more closely resembles the traditional role of Citizens Advice in the UK, rather than an ombudsman.

What is interesting is the way they are embedded in each local community. With an average age of 69 years old, and half of them being retired local government officials or teachers, each Counsellor has a history of being active within their community. They often set up a desk at supermarkets, community centres, and local festivals to receive complaints, and give lectures in schools to raise awareness. And in a country prone to natural disasters, they often play a key role in the aftermath of an earthquake, tsunami, or typhoon in providing support and information.

The Indonesian Ombudsman is perhaps a more recognisable classical public sector ombudsman, in relation to its structure and independence from Government. The issues they face relate to having limited resources to service a complex and diverse country, with a population of 279 million (the 4th highest in the world) spread across 17,000 islands, with thousands of distinct native ethnic groups, and over 800 different languages. Yet despite significant disparity in socioeconomic development across the archipelago (or perhaps because of it), complaints to the Ombudsman have stagnated at less than 9,000 per year between 2018-2023.

The ‘Sahabat Ombudsman’ system, or ‘Friends of the Ombudsman’, that they have developed is an attempt to encourage engaged and active citizens to help provide oversight of public service delivery. Building on a system of public service supervision training and / or internships, participants are then encouraged to form peer groups in their own communities – typically high school students, university students, journalists, and women’s community groups - to raise further awareness of the National Ombudsman within the wider community, and often armed with smartphones, highlight issues with day-to-day services immediately with local authorities.

The programme, which now consists of 5,000 individuals, has been a clear success; over 30% of the complaints the National Ombudsman now deals with come via the ‘Sahabat Ombudsman’ and have resulted in changes to the Driving License test and to the implementation of school uniform policies that reflect religious tolerance.

Whilst both Japan and Indonesia have characteristics that differ from the societies our members operate in, the two examples show that the concept of using motivated volunteers works in communities of both low and high socioeconomic status, in both rural and urban areas, and can successfully utilise either young people or retirees.

There were several other interesting sessions at the IOI Conference. The European Ombudsman, Emily O’Reilly, gave a typically powerful speech on ‘value dilemmas’, stressing that resilience and belief are just as essential as independence, and highlighting that a crisis rarely happens overnight, but builds over time as ‘small’ failings are ignored. Kholeka Gcaleka, the South African Public Protector, gave an inspiring talk on the challenges that a new ombudsman faces and how to deal with them. Both the Dutch Children’s Ombudsman and the Children’s Rights Commissioner for Flanders highlighted the need to raise awareness of the rights of children and the approach that ombudsman schemes and other institutions should be taking when making decisions about children.

And of course, the conference provided the opportunity for the OA’s members to share their work, with Margaret Kelly and Rosemary Agnew’s presentation of the work SPSO and NIPSO have been exploring in the ‘Reaching out to people with trauma’ session being particularly well received. The conundrum that asking someone to ‘make a complaint’ when they are experiencing trauma and extreme vulnerability, rather than helping them directly, can often feel inappropriate or simply not ‘customer focused’ resonated with many. Whilst the speakers admitted they do not yet have ‘the answer’ to that quandary, it’s a topic that the sessions at our own conference in June will no doubt keep at the front of people’s minds.